So, what have we really achieved on climate change?

Almost every week, we hear of government ambitions to address global warming. But what action are our politicians actually taking – and what impact is it having? Lewes resident and former scientific researcher and advisor on climate and energy Dr Martin Meadows takes a look.

Almost every week, we hear of government ambitions to address global warming. But what action are our politicians actually taking – and what impact is it having? Lewes resident and former scientific researcher and advisor on climate and energy Dr Martin Meadows takes a look.

The world is in an accelerating climate crisis. The good news is that few governments and corporations now deny its existence. The bad news is that we face a new type of denial: a discourse of delay and avoidance. Comforting rhetoric and long-term promises of change are substituting for the immediate, transformational action dictated by the physics of the atmosphere. The promises and actions are woefully short of what’s needed to halt global warming. That’s dangerous.

We can’t negotiate with the atmosphere.

How did we get here?

Firstly, a bit of background. In 2015 in Paris, all world leaders agreed that global warming above 2°C was extremely dangerous and must be avoided. They committed to keep global temperature rise well below 2°C and preferably to no more than 1.5°C. These goals require the cutting of greenhouse gas emissions at an unprecedented scale and pace. In turn that needs rapid global transformation in energy, buildings, transport, industry, land and the way the richer population consumes and uses resources.

The Paris Agreement is a political response to a challenge rooted in inflexible science. When it comes to climate science, there are three facts that really matter:

- when carbon dioxide (CO2) increases in the atmosphere, temperature rises;

- cumulative CO2 emissions (sum total of all emissions over time) primarily determine human-induced warming;

- accumulated CO2 stays in the atmosphere for over a century, possibly many centuries.

Think of it like a tap filling a bucket. The water level in the bucket represents the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. The water from the running tap is the CO2 that human activity adds to the atmosphere. Slowing the tap slows the rise in water level but only turning off the tap stops the water level rising. The practical consequence of these three scientific facts are stark and inescapable:

- every bit of CO2 humanity adds to the atmosphere raises the temperature for centuries;

- it is necessary to reduce global net emissions of CO2 to zero in order to stop the planet warming; and

- climate change is not an ‘end date’ challenge, as terms like ‘net zero by 2050’ imply. It is an accumulation challenge. To return to the bucket of water analogy, the challenge is to limit how much water there is in the bucket before the tap is turned off. Physics makes it necessary, if we want to avoid particular levels of global warming, to drastically cut emissions now and not wait for what might seem a convenient date in the future. If we’re unlucky – and scientific uncertainties about the response of the planet to accumulated CO2 pile up against us – the atmosphere may have already accumulated sufficient CO2 to cause global warming to exceed 1.5° If we’re lucky we may have a few more years at the current rate of emissions (see footnote 1).

What’s happened since Paris?

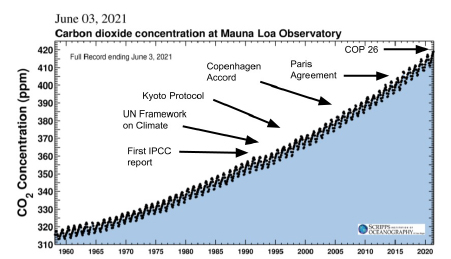

The chart below (known as the Keeling curve, after the scientist that started the measurements in 1958) shows atmospheric concentration of CO2, measured at a mountain top in Hawaii. The saw tooth variations in the line are due to the seasonal cycles of biological activity, such as plant growth and die-back.

Despite the agreements and accords over the last few decades – shown by the arrows – the line moves relentlessly upwards. The measurements are like a speedometer showing that the industrialised world still has its foot on the accelerator

Even with the COVID lockdown, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere continued to increase in 2020, reaching concentrations not seen for around 4 million years when the temperature was 2-3°C warmer and sea level was 10-20 meters higher than now. COVID just slowed the tap slightly for a short time. In 2021 the foot is back on the accelerator.

What’s next for the Paris Agreement?

The Paris Agreement requires nations to offer 2030 emissions reduction targets (known as pledges) that put the world on course to meet the Agreement’s goals. This process will happen at the Conference of the Parties meeting (COP26) in Glasgow in November 2021. It’s an important moment because it’s the first time since 2015 that nations will formally put forward their offers to cut emissions.

In the run up to COP26, China, USA, EU and the UK – amongst others – have pledged to cut emissions. That’s good news on the face of it but the reality is that the latest offers are nowhere near enough to meet the Paris goals. If governments achieve their pledges, end of century warming is estimated to be around 2.4°C, well beyond the 2°C ‘guardrail’. Even more worryingly, policies that countries actually have in place means the world is still on track towarm by a disastrous 2.9°C centigrade, perhaps up to nearly 4°C.

As things stand, there is a huge gap between plans to cut emissions and what’s needed. To have any chance of avoiding the worst of dangerous climate change, COP26 must result in further commitments by governments to rapid transformative action. In reality, if rich governments like the UK are seriously committed to the goals of the Paris Agreement, they need to achieve emissions cuts of at least 10% per year from 2020.

How is the UK doing?

Extinction Rebellion G7 protest at Seaford, June 2021

The global picture is bad. But is the UK doing better?

The UK’s performance is particularly important because the UK provides the President for COP26. That is a political role that puts the UK government in a pivotal position to influence the outcome of this November’s summit.

At first sight, the UK appears to be doing well. It was the first country to set legally binding national targets to cut emissions and the first major economy to set a net zero emissions target. The UK has reduced its national carbon footprint (greenhouse gas emissions associated with UK consumption) by around a quarter since 1997. We regularly hear of new records for low carbon electricity. In 2020, the government announced a ten point plan to accelerate the path to net zero.

All of which seems reassuring. But let’s kick the tyres.

Yes, we’ve made progress in decarbonising electricity. But electricity accounts for less than a fifth of our energy use. Most of our energy use is for transport, heating, food and other stuff we consume, which all remain big users of fossil fuels. Which means we have an unchanging reliance on fossil fuels. In 2019 78% of our energy came from fossil fuels – a proportion that’s remained roughly the same for some years.

Moreover, the government plans for us to continue using lots of fossil fuels for decades. For example, the government:

- has a road building strategy that if implemented will increase carbon emissions.

- has frozen fuel duty since 2010 resulting in 5% higher national carbon emissions

- plans the sale of fossil-fuelled cars until 2035 (including petrol/electric hybrid vehicles) and has no plans to phase out larger fossil fuelled vehicles or counter the rapid increase in the sale of larger, fuel inefficient cars, like SUVs. (See footnote 2)

- has closed after six months the only national homes insulation scheme

- continues to license new oil and gas exploration and maintains a strategy to maximise the recovery of oil and gas (despite an analysis from the International Energy Agency that concludes development of any new oil and gas fields is incompatible with temperature goals of the Paris Agreement.)

- supports the expansion of Heathrow and other airports

- is investing only 12% of what is needed to tackle the climate and nature emergency.

Indeed the government’s climate committee has reported that the UK does not even have policies to meet its legal targets for cutting emissions up to 2032, never mind its ambitions for net zero by 2050. In fact, taking into account a fair allocation of the amount of CO2 countries can emit and still be compliant with Paris goals, independent analysis concludes UK plans and policies are currently half what’s required.

The rhetoric has changed and net zero targets are in vogue. Little however has changed on the ground. Recent victories for climate campaigners over oil companies are encouraging – although some question whether real change is happening. What’s more, the government’s climate committee in June 2021 concluded that the government is failing to prepare the country for the inevitable impacts of global warming. This lack of action leaves us vulnerable to heat, flooding and disruptions to food and power supplies, amongst many other risks.

The reality of climate physics means we’re in danger. Meanwhile, we’re experiencing a tsunami of greenwash, rhetoric and promises. The atmosphere doesn’t respond to rhetoric and promises. Only turning off the CO2 tap will halt global warming. Until that happens, every tonne of CO2 emitted warms the planet for centuries to come.

That’s why we need radical change now from government and business.

Nothing else will do.

Footnote

- Estimates of the cumulative quantity of CO2 emissions that will commit the world to a particular level of global warming vary and are uncertain. The IPCC estimates that net zero must be reached in 20 years (with a range of uncertainty of +/- 15 to 20 years) from 2018 to avoid 1.5°C of warming, assuming global emissions start to decline in the decade 2020 to 2030. A separate study estimates that for a 90% chance of avoiding 1.5°C of warming, the world must reach net zero by 2023.

- Current policy is to phase out new cars and vans that are fuelled only by petrol or diesel by 2030 but to continue sale of hybrid vehicles until 2035. Hybrid vehicles use a combination of electric motors and conventional petrol engines. They emit CO2 from the tailpipe when using conventional engines, hence contributing to climate change. The government’s climate advisor has concluded that the 2035 phase out of hybrid cars and vans is not ambitious enough. The government plans to consult on an earlier phase out but has no firm plans to do so.

Thank you Martin for this wonderfully clear and succinct analysis. I will will using it to inform another letter to Maria!

Thanks Becky. Maria Caulfield doesn’t have to take your or my word for it. The Climate Change Committee published last week its assessment of the government’s progress to net zero. The publication was after copy deadline for my article so I didn’t reference it. The assessment is grim reading for the government and UK citizens relying on the government to protect them from the climate crisis.

https://www.theccc.org.uk/2021/06/24/time-is-running-out-for-realistic-climate-commitments/

Thank you Dr Meadows for a most succinct and cogent status report on Global Warming.

I do however wish to take issue with you on the contribution road building would make to increase carbon emissions and noxious gases.

Surely a more efficient road network enabling traffic to travel faster would avoid the excessive co2 output of engines idling or crawling along in low gears ( higher revs ) ?

A classic example is the A259 in rush hours.This is of course quite apart from the obvious economic advantages.

Great analysis that really sets out the urgency. I’d also flag the huge delays to the Environment Bill, and the fact the proposed Planning Bill seems also on course to give fine words whilst offering deregulation

A great article. Perhaps it can be used to fight more local threats, eg the threatened road-building in East Sussex, helping to give the wider picture and the dire situation to the local and national authorities who wish to continue expending fossil fuel.

By the way I thought it wold take several hundred thousand years rather than centuries for the CO2 global levels to ‘subside’ should the tap be turned off?

Hi Hilary.

Thanks for your comment. I hope readers can use it as evidence to fight local threats and also counter some for the delusional nonsense we hear from politicians and business leaders about climate change and what they’re doing to stop it.

The rate of recovery of CO2 levels is a complex topic and there is a range of estimates. I guess the key issue is when global warming will stop and how long it will be take for CO2 levels to reduce to ‘safe’ levels.

This article is a good summary of what will happen if and when humanity achieves net zero emissions. Good news is that warming will stop once net zero has been achieved. https://www.carbonbrief.org/explainer-will-global-warming-stop-as-soon-as-net-zero-emissions-are-reached

The bad news is that global temperatures will stay at the level reached at net zero.

The time taken to return to safe levels of CO2 and temperature will depend on the rate of uptake of CO2 from the atmosphere by natural processes and yet to be invented huge CO2 vacuum upper machines.

This is a great summary of the carbon cycle. https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/climate-change-science-solutions/climate-science-solutions-carbon-cycle.pdf